Remembering Jerry Angelich on Pearl Harbor Day

December 7, 2016 marks the 75th anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. In honor of this anniversary, I’d like to remember one of the heroes of that day.

Jerry Angelich, age twenty-five, a former baseball pitcher, ran to the wrecked plane, trying to wrestle loose a machine gun. He was at Hickam Field, Hawaii, near Pearl Harbor. It was Sunday, December 7, 1941, and the United States was under attack by the Empire of Japan. Burning wrecks of planes, trucks, and jeeps were everywhere, giant plumes of smoke rising from the battleship Arizona out over Ford’s Island. Angelich struggled to operate a machine gun from the destroyed aircraft as the noise, flames, and chaos of battle surrounded him . . .

Sources differ as to where he was born. Some reports state that he was born in the gritty southern California harbor town of Wilmington, on March 1, 1916. His Army enlistment records indicate that he was born in Butte, Montana. Regardless of his birthplace, his early life was spent in Anaconda, Montana, where his father, Milan, an immigrant from Serbia, owned a grocery store. He had an older brother, Dominick, and an older sister, Millie. His mother, Bozinea, also from Serbia, died sometime after his birth (and prior to the 1920 census), at which time Milan is listed as a widower.

The family returned to Southern California by the time Jerry was entering high school. He became a baseball star player at Banning High School, and by the time he was eighteen, Jerry was being followed by Major League Baseball scouts.

Two years after high school, while playing for the Sacramento Senators, a Double-A minor league squad, he was chosen to pitch in an all-star game against a traveling Japanese team, the Tokio (sic) Giants, on March 17, 1935. This was just a few weeks after his twentieth birthday, a heady honor for one so young. Although he pitched well, he suffered some wildness in the first inning, and that allowed the Giants to score two runs, which was all they needed for their 2-1 win.

His opposing hurler that day was Eiji Sawamura, an outstanding pitcher. The previous November, while only seventeen, Sawamura had taken the mound against an American All-Star team, and was credited with striking out future Hall-of-Famers Charlie Gehringer, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx, all in a row. Sawamura had an opportunity to play major league baseball in the US, but he chose instead to stay in Japan and later joined the Imperial Japanese Navy. On December 2, 1944, while serving aboard the ironically named cargo ship Hawaii Maru, he was killed when the vessel was sunk off the coast of Kyushu by the American submarine USS Sea Devil.

Jerry continued to play baseball into the late 1930s, pitching for such squads as the Provo Timps of the Industrial League, where he helped them win their league championship in 1939.

About two years later, with his chances for ever making it to the Major Leagues about gone, Jerry Angelich enlisted in the Army Air Corps. He entered the service on August 19, 1941, where he was assigned to the Army Air Corp’s 17th Air Base Group at Hickam Field. That fact that he was already on active duty at Pearl Harbor less than four months after enlisting is testimony to the desperate need for manpower experienced by the military at this time.

His official Air Corps records were typical for someone joining up just before the war began. He stated that his career was as an operating engineer for the last six years, at a salary of $60 per week. His emergency contact and beneficiary was his sister, now married, Mrs. Mildred Christofferson, of Wilmington; no mention was made of his father or older brother, who would have legally been considered his next-of-kin. His overall health was good; standing 6’1,” and weighing 175 pounds, with 20/20 vision and perfect hearing, he was more than acceptable to army recruiters.

And as he struggled to get the machine gun free, on what was to be called by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as “the Day of Infamy,” Japanese aircraft continued their attack. His apparent goal was to pull the gun loose and then use it to fire at attacking Japanese planes. But he was unsuccessful. Bullets from above struck the ground all around him. Jerry Angelich was killed in the rain of gunfire.

Private Angelich was buried two days later at the nearby Schofield Barracks Cemetery, the nature of his wounds not recorded due to the chaos of the day. His burial location was between two other men from his unit who were killed during the attack; on his left was Private Lawton J. Woodworth, of Syracuse, New York, and on his right, was Private Lawrence R. Carlson, of Oneida, Illinois.

His personal effects were typical; a safety razor, a can of shoe polish, a photo album, and similar items. As befitting his life as an athlete, there were also a catcher’s mitt, two baseballs, and a golf ball. In line with his tropical duty location, he also had three tan “aloha” shirts. They would eventually sent home to his sister, along with the Purple Heart which he was awarded.

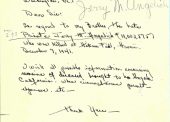

In June of 1942, Millie penned a letter to the Army requesting that her brother’s remains be brought back to Los Angeles, near her Wilmington home. The Army responded, “due to present conditions, no remains can be returned to the United States at this time.”

And so his remains rested in Hawaii for almost five years. Then, beginning in 1947, the military initiated the “Return of the World War 2 Dead” program. The next of kin of record for any serviceman buried overseas were given a choice. The remains of their loved ones could be permanently buried overseas, in a cemetery perpetually maintained by the US military, or they could be brought home to a stateside cemetery of choice. Expenses for any of these options were paid by the US government.

Millie Christofferson completed the Request for Disposition of Remains form provided by the Government on June 9, 1947. Apparently, she had changed her mind over the past five years and no longer desired the return of his remains to California. Instead, she chose that her brother be buried in the Punchbowl cemetery near Pearl Harbor. She requested that his headstone show Montana as his home state. He rests there to this day.

Jerry Angelich is remembered on the memorial wall located outside the entrance to the Lomita Post Office, in the small town of Lomita, CA. Although near where Jerry played baseball in Wilmington, I could find no specific connection between him and Lomita. But I’m glad he is remembered, wherever he is remembered.

As for me, I like to think of Jerry preparing to fire the machine gun at the attacking planes, as if he was standing on the mound, looking in to get his catcher’s signal. He gathers himself, ready to give all he has, and goes into his windup. Then, we see the ball streaking toward the plate, as we might have seen him fire that machine gun. The ball moves so fast that it can hardly be seen. Wherever he is today, Jerry has thrown another strikeout.

Ask Bill or comment on this story