Nicasio C. Sifuentes: One Week at the Front

(Company A, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, 4th Armored Division)

In the summer of 1944, as Allied forces fought to break free from the hedgerows of Normandy, losses mounted quietly and relentlessly. For many families back home, the war would be reduced to a single telegram, a short list of personal effects, and a grave thousands of miles away.

One of those men was Private Nicasio C. Sifuentes.

He was twenty-one years old.

From Westminster to War

Nicasio C. Sifuentes was born to Serafina and Maximino Sifuentes and raised in Westminster, California. By the early 1940s, he was working at the Ansco Company in Long Beach, a manufacturer contributing to the American war effort. Like millions of others, his connection to the conflict began on the home front—long before he ever carried a rifle.

In October 1942, he was drafted into the U.S. Army.

Within months, civilian routines were replaced by military ones: uniforms, training schedules, weapons instruction, and the steady reshaping of young men into soldiers. Sifuentes was assigned to Company A, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, part of the 4th Armored Division—a formation designed for speed, aggression, and constant movement.

England: The Long Wait Before Combat

In early 1944, the 4th Armored Division sailed for England to prepare for combat on the European continent. Like other elements of Patton’s Third Army, the division trained intensively across southern England, rehearsing for a battle no one yet fully understood.

While stationed in Wiltshire, Private Sifuentes was granted a five-day furlough. There is no record of how he spent it. Perhaps he traveled by train to London, only a few hours away. Perhaps he rested, wrote letters home, or simply enjoyed a brief pause before the unknown.

Whatever those days held, they would soon be eclipsed by events in France.

Normandy and the Hedgerow War

Company A entered combat in Normandy on July 13, 1944—more than a month after D-Day, but at a moment when the fighting was no less deadly. The Allied advance was bogged down in the region known as the hedgerows: thick earthen embankments topped with dense vegetation that turned every field into a fortified position.

For armored infantrymen, this was some of the most dangerous fighting of the war.

Progress was measured in yards. German defenders were hidden, well-entrenched, and determined. Firefights erupted suddenly and at close range. Artillery and mortar fire was constant. Units advanced, dug in, regrouped, and advanced again—often under direct observation from enemy positions just beyond the next hedgerow.

This was the environment Private Sifuentes entered.

Sainteny: One Week at the Front

Only seven days after Company A reached the front, disaster struck.

On July 20, 1944, near the village of Sainteny, Private Nicasio C. Sifuentes was killed in action. Six other men from Company A were killed the same day—an indication of how intense and sudden the fighting had become.

The official records do not describe the engagement in detail. They rarely do. What they confirm is timing and place: Normandy, mid-July, hedgerow country, one of the many brutal actions that never made headlines but steadily consumed lives.

Sifuentes had been in combat for just one week.

What He Left Behind

The Army recorded his personal effects with characteristic precision. They were few:

- A pair of fur-lined gloves

- A pair of civilian shoes

- Some English coins

Ordinary items, carried across an ocean and into combat, now reduced to entries on a form. Like so many soldiers, his possessions outlived him—becoming the final physical connection between a young man and the family who would soon be notified of his death.

Burial Overseas

After the war, families were given a choice: have their loved ones returned home or buried permanently overseas, among those with whom they served.

Serafina and Maximino Sifuentes chose to leave their son in France.

On February 11, 1948, Private Nicasio C. Sifuentes was laid to rest at the Normandy American Cemetery, overlooking the ground where the Allied invasion began and near the region where he lost his life. His grave joined thousands of others—rows of white markers standing in quiet testament to a campaign that cost dearly, even after the beaches were secured.

A Short Service, a Lasting Record

Nicasio Sifuentes did not live to see the breakout from Normandy, the relief of Bastogne, or the final drive into Germany. His war ended before the 4th Armored Division earned its most famous distinctions.

Yet his service belongs fully to that history.

The division’s reputation for speed and success was built on the efforts—and sacrifices—of men like him, who entered combat with little warning and paid the highest price almost immediately. His Individual Deceased Personnel File preserves the administrative record of his death and burial. This article restores the human dimension behind those documents.

Remembering Private Sifuentes

Private Nicasio C. Sifuentes was twenty-one years old. He was a factory worker, a son, and an American soldier who crossed the Atlantic to fight in a foreign land. He spent one week in combat and never came home.

His name does not appear in most histories of Normandy. But it appears where it matters—on a grave marker in France, in the Army’s records, and now in the preserved history of the 4th Armored Division.

That is why his story matters.

Photo Gallery

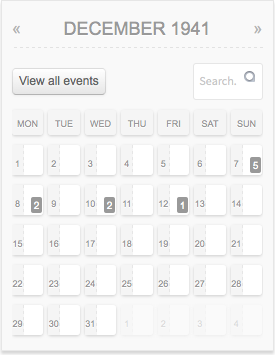

IMAGE 1 — Allied Might at Normandy Beachhead

American transports and landing craft crowd the Normandy shoreline as reinforcements and supplies pour ashore in mid-July 1944. As the Allied buildup pushed inland across the Cotentin Peninsula, divisions like the 4th Armored moved steadily toward the front lines where the fighting intensified daily.

U.S. Army / National Archives

IMAGE 2 — Allied Might at Normandy Beachhead (Detail)

An endless stream of trucks carries troops and matériel inland from the Normandy beaches, part of the sustained logistical effort supporting Allied advances against German forces in the hedgerow country. These movements were continuous during the same days Company A, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, entered combat.

U.S. Army / National Archives

MAGE 3 — American Tank Advancing Through Hedgerows

An American tank moves through a Normandy hedge in July 1944, equipped with a field-adapted hedgerow plow. Such improvised solutions emerged as U.S. forces confronted the deadly realities of bocage fighting, where every field and embankment could conceal enemy positions.

U.S. Army Signal Corps / National Archives

IMAGE 4 — Tank-Dozer Breaching a Hedgerow

A U.S. Army tank-dozer rams a hedgerow somewhere in Normandy on July 13, 1944—the very day Company A entered combat. Breaking through the thick earthen banks was essential to movement and survival, and often carried out under fire.

U.S. Army Signal Corps / National Archives

IMAGE 5 — GIs in a Field in France

American infantrymen move cautiously across open ground in France in late July 1944. Scenes like this defined daily life at the front: exposed movement, uncertain terrain, and constant threat from unseen enemy positions beyond the hedgerows.

U.S. Army Signal Corps / National Archives

Stories of the Men of the 4th Armored Division

This article is part of my series exploring the lives of men from the 4th Armored Division whose service records I have researched:

- PFC Oscar B. Oakman — Battery A, 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion

- Private Nicasio C. Sifuentes — Company A, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion

- TEC5 Genaro A. Caruso — Troop C, 25th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron

- Technical Sergeant Samuel K. English — Platoon Sergeant (MOS 651)

Each represents a single life within a division that helped change the course of the war—and paid for it, one soldier at a time.

Ask Bill or comment on this story