PFC Oscar B. Oakman: The Last Man to Die in the 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion

(PFC Oscar B. Oakman, 4th Armored Division, U.S. Third Army)

A famous photograph in the May 14, 1945, issue of Life magazine shows a soldier killed in Leipzig, described as “the last man to die in the war in Europe.”

But there never seems to be a last man to die in a war.

There is always one more.

Oscar B. Oakman was from Amaranth, Pennsylvania, near the Maryland border. Drafted at age 29, the self-employed farmer would have been one of the older men in his unit — the “older brother” among the younger soldiers around him. He entered military service in 1944 and was assigned to Battery A of the 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, a unit of the 4th Armored Division of General George S. Patton’s Third Army.

The 4th Armored Division is best known for its decisive role in breaking the German encirclement of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. In the months that followed, the division pushed relentlessly eastward through Luxembourg, Germany, and finally into Czechoslovakia — often in bitter winter conditions, and often under constant artillery and sniper fire.

Oscar Oakman was with them every difficult mile.

A Winter War with No Safe Places

The fight after Bastogne was not as widely remembered, but it was just as punishing. The Third Army crossed the Sauer River. It cut into the Siegfried Line. It advanced through German towns where every building could hide an ambush, every field could conceal mines, and every bend in the road might bring another burst of artillery.

The 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion played a critical role throughout — providing constant fire support as the 4th Armored’s tank and infantry battalions pushed forward. Artillerymen like Oakman were exposed far more often than people realize: firing positions were prime targets for German counter-battery fire, and moving guns forward under pressure was dangerous work.

By late April and early May 1945, the war in Europe was almost over. Units in contact still faced pockets of resistance, but German forces were surrendering in the tens of thousands. Town after town was giving up without a fight. Men allowed themselves to believe — carefully, quietly — that they might actually get through the last days unscathed.

It was during this brief, hopeful window that Oscar Oakman lost his life.

May 7, 1945: The Day Before the War Ended

According to the official Individual Deceased Personnel File (IDPF), Oakman was killed on May 7, 1945 — the very day Germany surrendered unconditionally to Allied commanders in Reims. The surrender would not take formal effect until the following day, May 8 (VE-Day), but for most American units, combat had effectively ceased.

The war was over.

And yet, for reasons lost to the chaos of those final hours — possibly stray German fire, possibly a delayed-action shell, possibly a tragic accident — Oscar Oakman was killed after victory had already been secured.

He was 30 years old.

His fellow soldiers would wake up on May 8th to news of peace. His family in Pennsylvania would receive the telegram no family ever wants. And Oscar would later be laid to rest in the Luxembourg American Cemetery, alongside so many others who also did not make it home.

When the War Ended for Everyone Else

This image tells the larger story with heartbreaking clarity. On May 9, the day after Oscar’s death, German units were marching peacefully into surrender lines stretching across Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Germany. Vehicles were parked. Weapons were dropped. Thousands of men were waiting to go into captivity rather than continue a hopeless fight.

It was all over — except for the families who would soon learn they were among the last to lose someone.

Oscar’s parents and siblings received his effects, his grave registration documents, and the formal notice of his death through the U.S. Army’s standard channels. These IDPF records preserve the details, but they cannot explain the loss.

There is never truly a “last man to die.”

There is only the one whose name you carry forward.

The Journey Home: A Story Told Through His IDPF

Following the war, Oscar’s mother, Delanie Oakman, requested that her son be returned to Pennsylvania. The Army’s Individual Deceased Personnel File (IDPF) — containing more than 30 pages — meticulously records the steps taken to honor that request.

Notification to his family

Between 1945 and 1947, Delanie Oakman exchanged letters and telegrams with the Quartermaster Corps to confirm her son’s identity, provide burial wishes, and sign transport authorizations.

(Request for Disposition of Remains, p.8)

Disinterment for return to the U.S.

Oscar was disinterred in August 1948. His remains were inspected and verified by identification tags and recorded as:

“Disarticulated, body complete. No fractures.”

(Disinterment Directive, p.3)

Transatlantic transport

He was shipped by the American Graves Registration Command from Antwerp to the Port of Philadelphia.

(Receipt of Remains, p.2)

Final burial

Oscar was buried on December 9, 1948, at Antietam National Cemetery, Grave 4421 — only miles from the Civil War battlefield where earlier generations of Americans had fallen.

(Headstone Request, p.11)

The Personal Effects He Carried

One of the most moving artifacts in Oscar’s IDPF is the Inventory of Personal Effects, listing the few belongings found with him:

- A pocket watch

- A fountain pen

- A small brown billfold

- Foreign coins from France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Czechoslovakia

- A silver pencil

- Two pocket knives

- Small keepsakes and souvenirs

(Inventory of Effects, IDPF, p.30)

These items — ordinary objects by themselves — became the final imprint of a life paused mid-journey. They were returned to his mother with the Army’s handwritten note:

“Effects received in damaged condition due to circumstances incident to war.”

Remembering PFC Oscar B. Oakman, 4th Armored Division

Though history books may not record his name, Oscar Oakman’s service is preserved through the work of researchers and the families who still honor his memory.

His story represents the thousands of men who fought until the final minutes of the war — and the heartbreak of those who were lost after it was already won.

When you walk the quiet rows of the Luxembourg American Cemetery, one of the markers belongs to Oscar.

He was not the “last man to die,” no matter what a magazine caption once claimed.

But he was someone’s last.

And that is why his story matters.

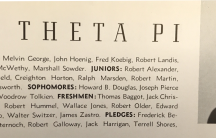

Photo Gallery

Image 1

Infantrymen advance under artillery fire near Pont-Le-Ban, Belgium, January 1945. Scenes like this were common across the front in the final bitter months of the war — the same conditions faced by PFC Oscar Oakman and the soldiers of the 4th Armored Division.

Image 2

American armored vehicles move through snow-covered streets in Belgium during winter operations. Column movements like these defined the daily reality of the 4th Armored Division as it advanced across Luxembourg and Germany in early 1945.

NARA 111-SCA-6402-001.

Image 3

Armored forces of the U.S. Third Army advance through snow during the drive beyond Bastogne. The 4th Armored Division remained in nearly continuous motion from December 1944 through the final days of the war, including operations that brought them into Czechoslovakia in May 1945.

NARA 111-SC-329954.

Image 4

German soldiers arriving at the designated surrender line near Karlsbad, Czechoslovakia, May 9, 1945 — the day after VE-Day. In nearly every direction across Europe, German forces were giving up peacefully. For PFC Oscar Oakman, the war ended one day too late.

NARA 111-SC-205668.

Stories of the Men of the 4th Armored Division

The following articles explore the service and sacrifice of individual soldiers whose records I have personally researched. Each reflects the character, courage, and complexity of the men who served in this extraordinary division:

- PFC Oscar B. Oakman

Battery A, 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion (FAB), from Amaranth, Pennsylvania. - Private Nicasio C. Sifuentes

10th Armored Infantry Battalion, from Westminster, California. - TEC5 Genaro A. Caruso (COMING SOON)

Troop C, 25th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, from Newark, New Jersey. - Technical Sergeant Samuel K. English (COMING SOON)

Originally from Molokai, Hawaii; trained at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey; Platoon Sergeant (MOS 651).

Each of these men’s stories reflects a single life within a division that helped change the course of the war.

Ask Bill or comment on this story